Na revista MIT Sloan Management Review do Inverno de 2024 encontrei o artigo "The Looming Challenge of Chemical Disclosures" de Lori Bestervelt, Colleen McLoughlin, e Jillian Stacy.

O artigo discute a crescente pressão regulatória sobre as marcas para compreender e divulgar a composição química dos seus produtos ao longo dos seus ciclos de vida. Isso inclui impactes desde a produção até ao destino final. O desafio reside na falta de conhecimento detalhado sobre os produtos químicos nas cadeias de abastecimento, uma vez que as actuais fichas de dados de segurança estão frequentemente incompletas. As marcas enfrentam dificuldades na obtenção de formulações químicas detalhadas dos fornecedores e precisam de investir em avaliações abrangentes dos perigos químicos. O artigo enfatiza a importância da transparência, da colaboração com fornecedores e da integração de avaliações de riscos químicos nos processos empresariais para uma abordagem mais sustentável.

Recordo experiência no sector do calçado em que vários fabricantes de produtos usados no processo de fabrico do calçado, como tintas e palmilhas, se recusavam a cumprir a lei no âmbito dos regulamentos comunitários abrangidos pelo REACH ((Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals). Portanto, enquanto uns vêem riscos, outros podem ver oportunidades para o negócio: A transparência e a colaboração entre marcas e fornecedores são essenciais para mitigar riscos e aproveitar essas oportunidades.

Agora são os Estados Unidos.

"New sustainability rules make consumer brands accountable for the composition of their products, but most companies are in the dark.

New and emerging rules in the U.S. responsible for the environmental impacts of products through their entire life cycles are forcing brands to confront a striking knowledge gap: their often inadequate understanding of the chemicals found in their supply chains.

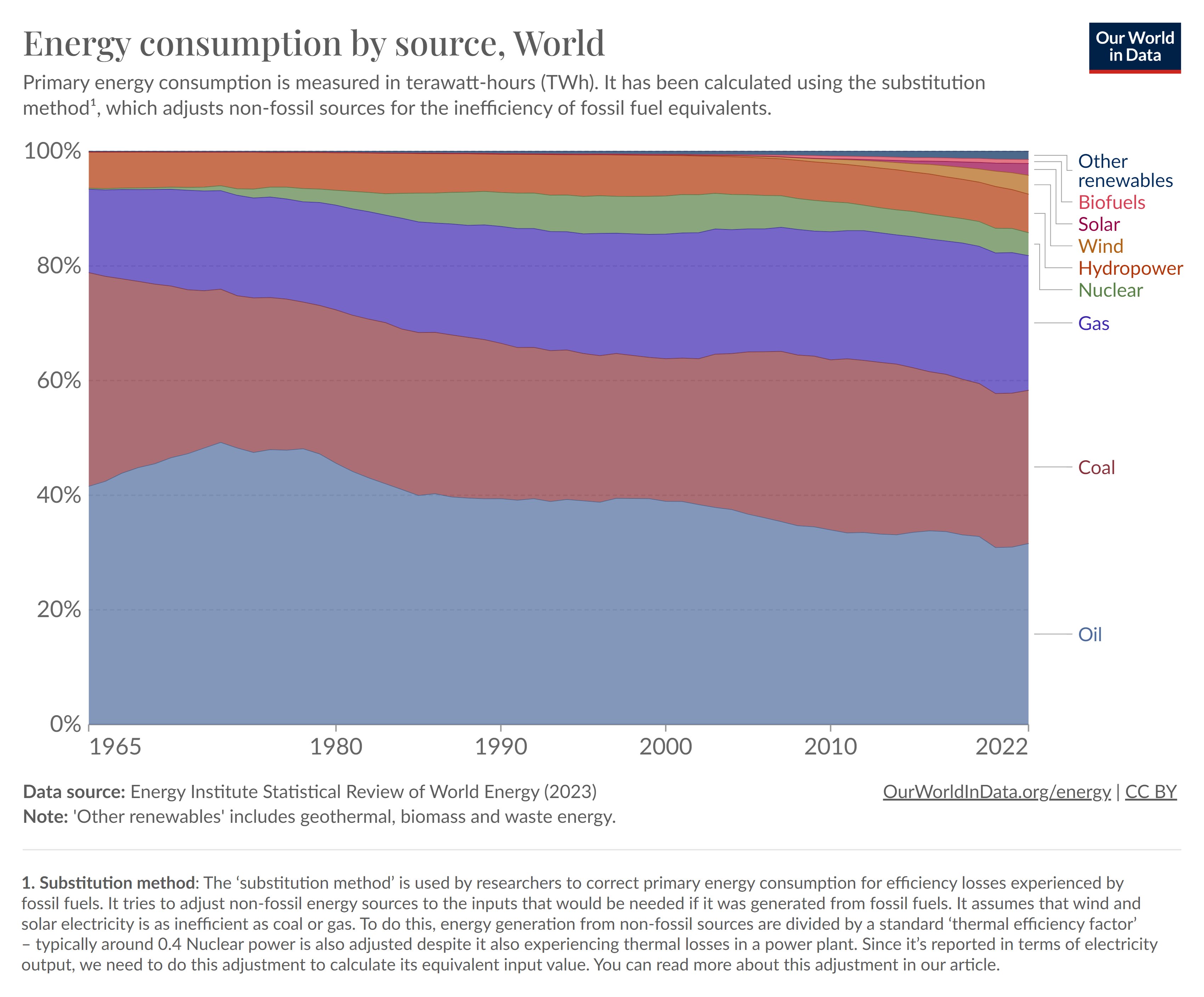

The European Green Deal's Circular Economy Action Plan, which was adopted in March 2020; newly proposed eco-design rules affecting fashion and textiles; and the proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive will require companies to disclose any risks to human rights and the environment. They apply throughout the product life cycle, from the formulation of ingredients and materials to product manufacturing, packaging and distribution, and recycling and disposal. In the U.S., four states — California, Colorado, Maine, and Oregon — have adopted extended producer responsibility laws aimed at packaging materials, and the issue will be a focal point of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's eventual Scope 3 supply chain requirements. On top of such legislation, a host of new regulatory actions focused on materials sourcing and disposal, safety in global supply chains, and the protection of employee safety and human rights are rolling out in jurisdictions around the world. These rules pose a challenge for many of the brands that manufacture, market, and sell the clothes we wear, the cosmetics we apply, and the toys our kids play with, because their companies have very little visibility into the detailed chemical composition of their products.

In the face of regulatory developments, fashion brands have had to reconsider their use of materials, dyes, and a host of chemicals that have been linked to deforestation and pollution. They also need to be able to trace these compounds through every link in the supply chain.

...

Most brands have relied on safety data sheets (SDSs) provided by their suppliers for information on product chemical composition. However, these documents are designed primarily to disclose information on chemicals and chemical compounds that could harm workers or others in the supply chain. They don't provide detailed information on the chemical composition of every material used in a product or offer any meaningful insight into its impact on recycling and disposal.

In our work conducting chemical hazard assessments and product toxicology analyses for some of the world's largest brands, approximately one-third of the SDSs we reviewed contained incomplete or inaccurate information on the chemical makeup of the products and materials they covered. Whether that is a result of suppliers intentionally omitting information or a reflection of the limitations of the SDS as a disclosure tool, the end result is that the brands responsible for these products are often in the dark about what's inside them.

Filling in the gap between the basic information provided in SDSs and the detailed disclosures that will soon be required by global authorities has become a source of conflict and confusion for many brands. Some suppliers are reluctant to share detailed chemical formulations to protect trade secrets, and many brands have been unwilling (or unable) to invest in costly chemistry assessments.

We expect that this problem will be addressed in two ways. First, the market will likely shift to suppliers that can attest to the safety of their products and processes.

...

Second, companies will have to invest in detailed chemical screening to provide more comprehensive hazard assessments and full formulation disclosures. This approach has also been gaining in popularity as brands seek certainty and an objective means of evaluating their suppliers.

...

The critical first step in the process of removing toxic substances from a supply chain is systematically identifying them. For example, we recently worked on a project with a global footwear brand that had a companywide mission to make its rubber supply chain more environmentally sustainable. It began by building a comprehensive database of its current chemical inventory and checking all entries against a list of known toxins and regulated chemicals in each jurisdiction in which it operates. Only then could it start the process of transitioning to safer chemicals.

As they make progress, brands need to build this institutional knowledge into their sourcing and product development processes to mitigate or eliminate the harmful chemical impacts of future products throughout their life cycles.

In the long run, these initiatives will result in safer, more sustainable consumer products. In the near term, however, expect to see a great deal of disruption and reshuffling of supply chains as more brands start to recognize that the tried-and-true methods of manufacturing and distribution are no longer sufficient in today's sustainability-oriented economy."

A verdade é que cada vez mais nas minhas relações encontro pessoas que fazem escolhas com base nestes pressupostos. Por exemplo, na comida:

- uma embalagem de canela da marca Continente;

- amêndoas da Califórnia;

- sementes de girassol da China.

Há anos comprei um mini-rato de computador numa loja chinesa em Estarreja, ao fim de 15 dias tinha "escamas" na mão direita.

Quantas empresas vão colocar este tema na sua próxima análise de contexto?

%2006.21.jpeg)