Há muitos anos que aqui no blogue escrevo que os políticos e os empresários, na generalidade, são iguais. São iguais porque emergem do mesmo caldo, do mesmo magma cultural.

Os políticos só são mais perigosos porque lidam com os recursos que são da comunidade e, por isso, são em maior quantidade e, mais grave ainda, não têm skin-in-the-game, esbanjam impunemente o que não lhes custa a ganhar, porque ser estúpido ou ignorante não é ilegal (fora o dolo). O impacte dos seus erros leva países inteiros à falência, o impacte dos erros de um empresário apenas levam a sua empresa à falência.

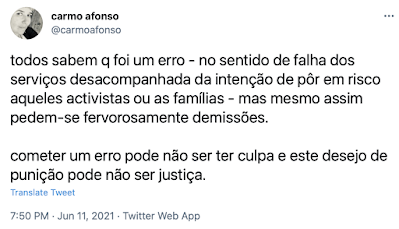

Agora reparem nisto, a propósito da polémica recente sobre a Câmara Municipal de Lisboa:

Pensem, como seria/será uma empresa gerida assim?

Perante asneiras, perante maus resultados, perante reclamações, responder com resignação:

"NÃO DEVIA ACONTECER, NÃO DEVIA TER ACONTECIDO E ESPERA-SE QUE NÃO VOLTE A ACONTECER"

Este "espera-se que não volte a acontecer" é tão ... inclassificável. É o pior da cultura portuguesa. Acreditar que basta ter fé, para que não volte a acontecer. Foi azar! (Há um ditado, francês, que diz qualquer coisa como: é bom que o marinheiro tenha fé, mas também convém que reme)

Outra vez, como seria/será uma empresa gerida assim?

Claro que há empresários que não partilham desta cultura. Por exemplo, o meu parceiro das conversas oxigenadoras. No Whatsapp escreveu-me recentemente:

"Quando fui a São João da Madeira tomar a vacina estimei uma cadência de 15 vacinas por hora/guichet e o centro abriu 45 minutos depois da hora.

...

Enquanto estive à espera, fiz esta projeção, que por baixo poderiam vacinar um minimo de 600, em vez das 480 atuais. Mas numa abordagem mais detalhada, seria possível melhorar mais e com melhor serviço para os clientes e para os enfermeiros."

Gente que olha para os desafios e procura estudar os factos para mudar a realidade e, assim, aspirar legitimamente a resultados futuros desejados diferentes.

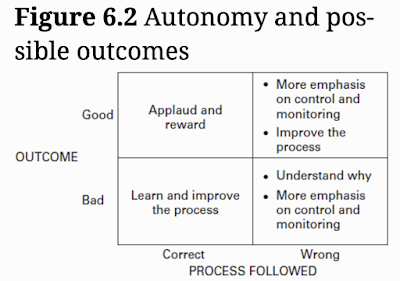

Entretanto, ontem à noite durante mais uma leitura de “Organizing for the New Normal” de Constantinos Markides, apanhei isto:

A conjugação "bad outcome x wrong process followed" não obriga a mudar o processo, implica mais controlo... como não recuar mais de 10 anos até isto:

"As instituições que, analisando um qualquer acidente, se ficam pelo modelo de “culpa individual” perdem a possibilidade de alterar o “sistema” e melhorar a segurança pela introdução de novas políticas que tornem novos erros menos prováveis. Ao punir, simplesmente, um indivíduo a organização nega de forma subliminar a sua responsabilidade no evento negativo, mas não o corrige verdadeiramente. É o princípio da negação dos acidentes, que caracteriza as organizações demasiado burocratizadas e sem abertura a qualquer processo de inovação regenerativa. Face a um acidente que ocorre, a tendência é isolá-lo, punir o responsável mais directo, impedir a divulgação do facto e, seguir em frente, após ter tomado medidas limitadas a nível local."

Imaginem as implicações da conjugação de "bad outcome x correct process followed"... o trabalho, a mudança necessária, as complicações... e mais, neste caso não há erro!

Erro existe quando o processo não é seguido! Os serviços não falharam, os serviços cumpriram o que estava previsto.

Quando um mau resultado surge naturalmente de um mau processo, a responsabilidade é de quem tem autoridade para desenhar e aprovar processos. Imaginem uma empresa que não esteja atenta à evolução da legislação (RGPD, por exemplo), também pode argumentar em sua defesa que foi um erro, que foi um lapso?

Há tempos vi como uma empresa tinha tratado a reclamação de um cliente. No fim, concluíam que a empresa não tinha qualquer responsabilidade. O problema tinha sido gerado por um subcontratado.

Uma excelente forma de evitar... o trabalho, a mudança necessária, as complicações, o olhar para dentro...

Ainda argumentei: Come on, o cliente não quer saber do subcontratado, o acordo dele é convosco. Não precisam de mudar nada? Nem a forma como escolhem subcontratados? Nem a forma como informam, apoiam ou controlam subcontratados?

%2006.21.jpeg)