...

while it takes 250 people to make 1,000 pairs of jeans in Vietnam, in Vernon it takes less than 100.

We’re creating a hybrid manufacturing model that could be a formula for the industry.

“There is always a point in time when technology is ready,” Bahl said. “We’re creating a hybrid manufacturing model that could be a formula for the industry.”

...

For a start, making jeans at the facility will allow brand partners to burnish their ethical credentials and signal their support for American jobs. But it could also make smart commercial sense. With small-batch production options and proximity to American consumers, Saitex’s Vernon plant enables brands to quickly replenish inventory, responding to consumer interest for particular products rather than placing big bets upfront. That means better aligning supply and demand, with the hopes of significantly reducing excess inventory.

Plus, there’s a test-and-learn opportunity. For instance, a brand can send the factory a new denim design and have just 500 pairs produced for trying out with consumers. Based on hard data, the brand can then choose whether or not to scale up production. In traditional apparel manufacturing, it can take up to a year for a product to go from concept to sales floor. Working with the new Saitex facility, it could be as little as three weeks. For e-commerce orders, Saitex offers brands a service that also ships their products directly to the consumer, further speeding up the process.

“This factory will allow for real-time data and real-time ROI,” Bahl said. “Think 90 days versus 270 or 365.”

Some believe the launch of factories like this mark a tipping point in the way clothes are made.

...

Interest in responsive, or “just-in-time,” manufacturing — successfully deployed by Spain’s Inditex, parent of fast-fashion giant Zara, which famously moves product from concept to sales floor in two-to-three weeks — has gathered steam in the US over the past decade.

As a result, the US has experienced a small-but-steady uptick in local apparel and shoe production. In 2019, 98 percent of shoes and 97 percent of clothes bought by Americans were imported, but the number of these products manufactured locally increased by 72 percent over the previous 10 years, according to the American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA), a trade group.

“These aren’t bringing back jobs that left decades ago,” said Stephen Lamar, president and chief executive of the AAFA. “Instead, it’s creating jobs that are driven by technology.”

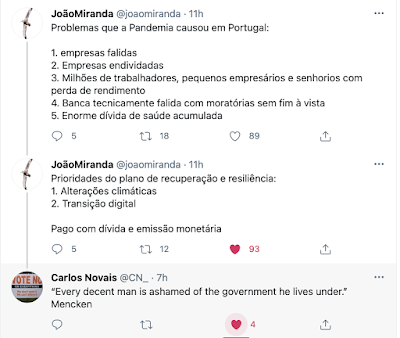

[Moi ici: Segue-se um trecho com novidades interessantes] Scaling these efforts has been challenging, however, in part because many retailers have a vested interest in the old way of doing things. For some, cheaply produced, large-inventory volumes can help to weave a growth narrative for investors, where retailers claim they are manufacturing more products in order to open more stores and fuel top-line sales. The success of the off-price channel has shown that this approach can work, allowing brands to increase sales for years while maintaining slim margins.

But now, brands have so much excess inventory — especially after 2020 hit consumer demand and forced many to shut down their physical stores — that prices often can’t go any lower, nor discounts any deeper, without resulting in losses.

“That growth has either disappeared or is highly uncertain,” Thorbeck said. “Without that engine of growth, the formula for cheap inventory is an unsustainable burden.”

Even so, convincing brands that produce en masse to implement on-demand manufacturing remains an uphill battle. For one, it requires upfront investment. It also costs more per item to manufacture in small batches, a hard hump to get over, even though items made this way are more likely to be sold at full price, resulting in increased profits.

Brands like Nike and Adidas, which have opened on-demand manufacturing facilities in recent years only to close them, often aren’t willing to take the risk, even if it means a leaner, more efficient business in the medium to long term.

...

...

Thorbeck is convinced that the pandemic’s squeeze on margins is the push that retailers needed to modernise their operations.

The alternatives have been exhausted.

“I’m optimistic because honestly, the alternatives have been exhausted,” he said. “Companies have not dramatically improved retail performance, and their only growth channel, which online, is inherently more expensive.”"