"Generating distinct options is even more difficult when our minds settle into certain well-worn grooves. Two of those grooves are common states of mind, studied widely by researchers, that play a role in almost every decision we make. One is triggered when we think about avoiding bad things, and one is triggered when we think about pursuing good things. When we're in one state, we tend to ignore the other.

To illustrate one of these states of mind, imagine a morning that goes as follows. Your teenage son talks to you about his duties as the president of a service-minded student club. You're proud of him, but you also hope he understands the commitments he's made. In your driveway, you bump into your next-door neighbor, who mentions that a home down the street recently sold, after six months, for far less than its asking price. On the way to work, you listen to a radio program about the potential dangers of a newly emerging technology.

Then, an hour after you arrive at the office, your boss pulls you aside and tells you about a new position that has opened up. It involves leading a small team in creating and launching a new product. It's a pretty risky product concept, but your boss thinks there's solid potential. He wonders if you'd be interested—it would involve a lateral move, with fewer direct reports than you currently have but potentially more glory if everything goes well.

What's your gut reaction to the offer? You might feel a little cautious. It doesn't really sound like a promotion, and you have a responsibility to get your team through its current project. And what happens if the new product is a flop? Will you have sabotaged your career prospects? You will definitely want to consider the position carefully. Better safe than sorry.

Now imagine a different morning. Your son tells you about his aspirations for a club he joined at school; you feel parental pride that he's pursuing big goals. Your neighbor tells you about how much he loves his herb garden, which gets you thinking about some landscaping ideas for your own backyard. On the way to work, you listen to a radio program about the opportunities opened up by a newly emerging technology. An hour after you arrive at work—the same as before your boss tells you about a new position ...

Now what's your gut reaction to the position? This time, you might feel a bit more open and enthusiastic. You're being trusted to lead a new product with great potential! Nothing ventured, nothing gained.

How you react to the position, in short, depends a great deal on your mindset at the time it's offered. Psychologists have identified two contrasting mindsets that affect our motivation and our receptiveness to new opportunities: a "prevention focus," which orients us toward avoiding negative outcomes, and a "promotion focus," which orients us toward pursuing positive outcomes.

In the first scenario above, you arrive at work with a prevention focus, which means that you are in a vigilant mood. You want to ensure that your son lives up to his duties. You're worried about your home losing its value. You really hope policy makers will stave off the dangers of the new technology. So when you think about the new position, your spotlight tends to highlight what could go wrong, what you could lose. Whereas in the second scenario you have a promotion focus, meaning that you are eager rather than vigilant—you're open to new ideas and new experiences."

Os mesmos eventos são percebidos de forma diferente. A principal conclusão é que o nosso estado de espírito no momento da tomada de decisão influencia grandemente a nossa reação às oportunidades e desafios. Como não recordar a comunicação social no tempo da troika e no tempo da geringonça.

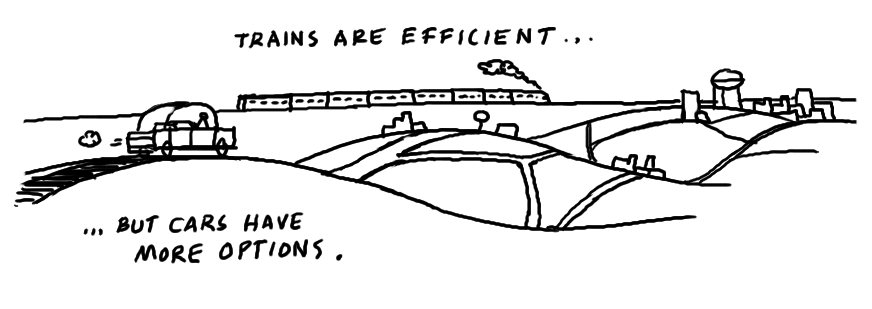

Humanos perante os mesmos factos. Não, adultos perante os mesmos factos. Como será o modelo mental:

%2006.21.jpeg)