"analisando os dados sectoriais, o grande destaque, a meu ver, é para o segmento plásticos. um crescimento de 10,5% em 2013 é fenomenal! pensar que em 10 anos este sector teve a evolução que teve é absurdo quase. e mantém-se essa pujança, e anunciam-se novos investimentos. fenomenal."Recordei-me desta história que li há pouco tempo:

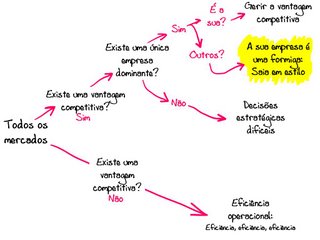

"That’s what Andrew Liveris, the CEO of Dow Chemical, demonstrated when he bet the future of his business on the acquisition of Rohm and Haas in July 2008. Liveris saw changes brewing in the chemicals industry. Looking outside in and future back, he realized that sooner or later the playing field would tilt away from Dow’s long-held strengths. For decades it had been the dominant player in the commodities chemical business, processing crude oil into a range of petrochemicals sold to a multitude of industries. But new players from Asia and the Middle East were coming into the industry. At the same time, oil producers were getting interested in businesses that processed their raw materials. Liveris imagined how a direct competitor like SABIC, whose majority shareholder is the Saudi Arabian government, might combine with a Saudi Arabian oil producer’s drive for vertical integration. (Moi ici: Essa foi uma das diferenças que senti na minha vida profissional. Entre 1987 e 1993 estive ligado à indústria química de polímeros e nunca vi nada a sério a vir de marcas associadas aos países produtores de petróleo no Médio Oriente. Havia alguma coisa do México e da Venezuela... e até de Israel. Em 2003, voltei ao mundo dos polímeros ao fazer consultoria para uma empresa. E a marca SABIC entrou no meu vocabulário). He concluded that advantages in access to and pricing of crude would make it all but impossible for Dow to retain its number one position in the low-margin commodities business. Because of its pricing disadvantage, Dow couldn’t win in the new game, and at some point the company’s market value would decline. Liveris saw a brighter future for Dow in higher-margin specialty products. To win in that area, it would have to strengthen its limited capability. This would be the very essence of a big bet, requiring Dow to radically shrink its mainstay business in favor of something that was only a minor part of its business. And the bet had to be made quickly, ahead of the competition and before Dow’s market value took a nosedive. The Rohm and Haas acquisition would shore up Dow’s capabilities in specialty chemicals, but at $18.8 billion the all-cash deal required more than Dow had. Now Liveris had to really stick his neck out, tapping out Dow’s resources and patching together financing. To fill the gap, he signed an agreement for a joint venture with Kuwait’s state-run Petrochemical Industries Company (PIC), which would infuse Dow with $9 billion to partly finance the deal. It was the first joint venture between the two parties, and Liveris’s plan to acquire Rohm and Haas hinged on its success. Liveris had the stomach to make the strategic bet, which rested precariously on the deal with PIC.É voltar ao esquema:

…

Today specialty chemicals make up about two-thirds of Dow’s revenue, up from 50 percent before the merger, and Liveris says he is aiming to tilt the mix toward 80 percent.

…

If Liveris hadn’t been thinking outside in and future back, if he hadn’t had the courage to acknowledge that control of crude oil by foreign governments would favor Dow’s competitors, he would not have seen the need to make a sudden move, especially when he did. He positioned the company for the new game that was just beginning to take shape, not the old game Dow had already played. And while Dow’s move caused others in the industry to reconsider their positioning and competitive edge, it was far enough ahead that it didn’t have to fight its way through a bidding war. Earnings have become less volatile since then: Dow was able to raise prices 5 percent in 2011, which more than offset increases in purchased feedstock and energy costs."

E perceber que existe uma vantagem competitiva clara no mundo das commodities, o preço mais baixo, e perceber que nunca poderemos jogar essa cartada com vantagem e, por isso, o melhor é preparar uma saída em estilo e procurar outros negócios.

Trechos retirados de "Global tilt: leading your business through the great economic power shift " de Ram Charan.

%2006.21.jpeg)

1 comentário:

boas meu caro!

excelente reflexão. mas no caso da evolução positiva das exportações de plásticos em Portugal, creio ter mais a ver com "produtos de plásticos".

fabricantes de utilidades domésticas, embalagens, tubagens, etc. conheço vários casos.

aliás, a própria Inditex tem em Portugal alguns dos seus fornecedores de embalagens, e comprar cá uma enorme quantidade de material.

conheço alguns exemplos de empresas produtoras de bens de plástico que são verdadeiras "campeãs escondidas", como gosta de referir. aliás, a Vipex é uma delas.

a grande questão aqui é mesmo a incapacidade de controlar minimamente o custo da matéria prima, de resto, é uma área de negócio interessante. e o plástico tem cada vez mais utilizações.

seria óptimo que o segmento dos plásticos em Portugal se desenvolvesse muito mais, até porque um dos "problemas" do segmento dos moldes é exactamente o sector dos plásticos não estar tão desenvolvido. ou seja, ter acesso privilegiado a moldes como existe em Portugal, é uma vantagem competitiva real dos nossos plásticos. quanto mais estes se desenvolverem, mais beneficiam os moldes. um verdadeiro efeito "spill over"

Enviar um comentário