Ontem de manhã, enquanto conduzia a caminho de Guimarães, ouvia nas rádios falar-se da produtividade e do salário mínimo. Tantas generalidades... até me arrepiei. Até me lembrei de uma das cenas mais anedóticas deste blogue, a superior produtividade portuguesa no Luxemburgo, segundo um embaixador do Luxemburgo em Portugal é motivada pela saudade. A sério, não estou a brincar.

Uma das perguntas que não obteve resposta foi: porque é que o salário mínimo e o salário médio estão a convergir?

Primeiro, um exemplo do calçado. O preço médio do calçado exportado em 2020 foi de 27,80 USD. Conheço algumas empresas com um preço médio do calçado que produzem e exportam na casa dos 52 USD. As empresas que vendem a 52 USD pagam salários mais ou menos iguais às que exportam a 27,80 USD. As empresas pagam o que o mercado está a pedir e o que o mercado pede é o que a média das empresas do sector consegue pagar. É uma espécie de lei inversa da que se passa quando um nigeriano, motorista de autocarro, emigra para a Noruega para conduzir autocarros. faz exactamente a mesmo coisa, mas por causa do contexto diferente, passa a ganhar cerca de 16 vezes mais do que na Nigéria. Enquanto não se deixarem morrer as empresas menos produtivas não sairemos da cepa torta.

Toda a gente pensa que a diferença de produtividades entre Portugal e a Europa Ocidental tem a ver com eficiência ... come on!!! A diferença resulta de se produzirem coisas diferentes. Recordar "Acerca da produtividade, mais uma vez (parte I)"

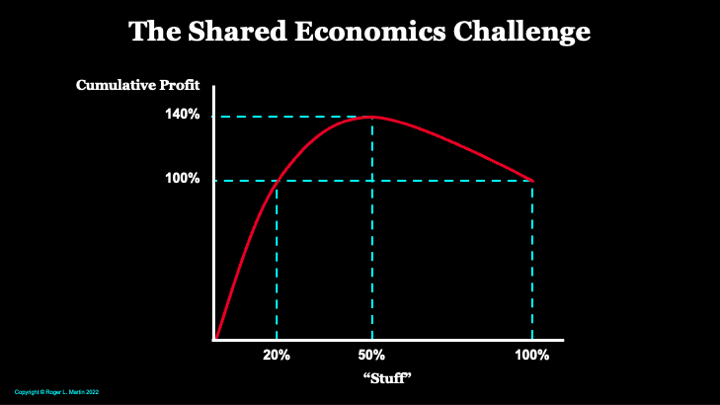

Em The "flying geese" model, ou deixem as empresas morrer!!! apresentei a figura:

Reparem como a evolução em cada país se dá quando o grosso do capital e dos trabalhadores avança para outro sector, capaz de suportar margens superiores. Reparem como a evolução não é de vestuário low-cost para vestuário high-price. Ela existe, mas é marginal (recordar a

não-bruxaria de ontem). Eu, como consultor, a trabalhar com uma empresa individual que não tem de salvar o país, que tem de fazer pela sua vida, posso apoiar o processo de descoberta e construção que permite que uma empresa tradicional continue num sector tradicional,

como o denim japonês, o mais caro do mundo, com margens superiores. No entanto, isso não é escalável para todo um sector.

Verdade, algumas empresas conseguem fazê-lo, a fabricante de botas de borracha acabou a fazer telemóveis da marca Nokia, ou a Wartsila que começou como uma serração, mas são as excepções à regra. Pela enésima vez vou colocar aqui o que aprendi com Maliranta talvez em 2007, é a primeira citação na coluna de citações à direita do blogue:

""It is widely believed that restructuring has boosted productivity by displacing low-skilled workers and creating jobs for the high skilled."Mas, e como isto é profundo: "In essence, creative destruction means that low productivity plants are displaced by high productivity plants." Por favor voltar a trás e reler esta última afirmação."

Moisés disse ao faraó: Deixa o meu povo partir!

"IBM is shedding IT services, once a cornerstone of its 1990s recovery.

...

IBM’s IT service business is labor intensive. It has 90,000 employees generating sales of $19 billion, which translates into just over $200,000 per employee. On average even Wal-Mart staff bring in more money. Once the spin-off is completed, IBM can concentrate on higher margin cloud software and solutions.

...

The value creation lens makes it obvious that the IBM spin-off—similar to the other headline grabbing announcements—is fundamentally a decision to move out of an unattractive position. In 2016 Microsoft actually did the same when shutting down the phone hardware business it previously bought from Nokia."

O mesmo artigo refere que a Johnson & Johnson também pretende avançar com um spin-off. Interessante, este blogue tem registado uma década nada abonatória nessa empresa. Recordo "

Dá que pensar..." como o exemplo das empresas que abandonam a inovação e se concentram na eficiência operacional, o tal fenómeno do

hollowing.

Recordar Terry Hill e o

Verão de 2008:

"the most important orders are the ones to which a company says 'no'."

Como é que está lá em cima?

"Once the spin-off is completed, IBM can concentrate on higher margin cloud software and solutions."

Quando não se corta com os produtos do passado, não há foco suficiente no futuro. Por alguma razão Cortez queimou os barcos...

Querer aumentar a produtividade, ao mesmo tempo que se apoiam as empresas com baixa produtividade... não vai dar em nada.

Agora imaginem a empresa que estando bem, resolve fazer o que a IBM vai fazer, concentrar-se em produtos de margens mais elevadas. Como não existe mercado para comprar a parte "clássica" da empresa, a empresa teria de encolher. Imaginem as manifestações contra uma malvada empresa que estando bem, resolve cortar postos de trabalho e abandonar bons clientes para poder aumentar a produtividade...